Survival of the Godliest

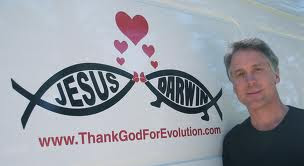

Image source: here I don't often cite articles, especially ones that are about religion, but this one I find fascinating. For those of us who pay attention to future possibilities, this could be a harbinger of a coming sea-change in the centuries-long tensions between science and religion. And in this scenario science doesn't win. This blog article caught my eye because if we were living in a rational world one might imagine that support for the scientific study of unusual human experiences, including psi and mystical epiphanies, would be strongest among secular humanists, whose faith is in science (sort of). Unfortunately this is not the case, at least not among those who most vigorously wave the banner of secular humanism and proudly call themselves as "skeptics." They tend to view parapsychology as an illegitimate use of science to support religious beliefs. This is not true and never has been. But that's what they believe. Religious people, by contrast, see